Kōwaowao and mountain hounds tongue fern can germinate on host trees and grow without a connection to the forest floor. In contrast, mokimoki climbs tree trunks and always maintains a connection to soil.

|

Microsorum is a genus of ferns that has members in Africa, India, China, Madagascar, south-east Asia, Australia, some south Pacific Islands and, of course, New Zealand. "Microsorum" refers to the small sori (clusters of spores) on the underside of the leaves which are a splendid orange-brown colour. Our Microsorum trio all grow epiphytically but can also occur on the ground/rocks. The trio consist of the endemic mountain hounds tongue fern (Microsorum novae-zealandiae) and two species that we share with Australia: kōwaowao (M. pustulatum subsp. pustulatum) and mokimoki (M. scandens). All three species have thick creeping rhizomes from which leaves on thin stipes emerge. The fronds are often variable, ranging from single, linear fronds to ten or more thin lobes (pinnae). Mountain hounds tongue fern only occurs in the North Island. It has beautiful golden scales along its rhizome and the largest fronds of the three species. Kōwaowao has the broadest frond lobes within which very distinct veins are visible. The rhizome of this species can be blue-green with brown spots. Mokimoki is known as 'fragrant fern' because the fronds have '...an agreeable delicate scent' (Colenso 1892b). The juvenile, undivided fronds can often look like frills on the trunks of tree ferns.

Kōwaowao and mountain hounds tongue fern can germinate on host trees and grow without a connection to the forest floor. In contrast, mokimoki climbs tree trunks and always maintains a connection to soil.

0 Comments

The epiphytic flora of New Zealand has interesting similarities with the epiphytes of tropical rainforests. For example, we have diverse epiphytic species that belong to many different plant groups: ferns, orchids, shrubs etc. However, these groups of plants also have stark differences and today's example is the cacti! Forget what comes to mind when you imagine a cactus because the cacti of tropical Americas do not grow in sand nor do they have large spikes. Species such as those belonging to Rhipsalis grow as epiphytes and have long leaves without any spikes. They also have tiny flowers and fruit that emerge from the leaves. Species of Rhipsalis are thought to have specialist relationships with one group of tropical birds. A recent study by Guaraldo and colleagues compared the requirements for Rhipsalis seed germination to that of mistletoes; a plant group that is considered to rely on specialist dispersers. Both of these plant groups have sticky seeds that are most successful if they are stuck in the fork of a large branch with suitable bark. Species of Rhipsalis are even known as "mistletoe cactus" because the fruit are so similar. Interestingly, the seeds of Rhipsalis and mistletoe species are both primarily distributed by Euphonia birds. These birds do a good job of establishing sticky seeds because they smear the seeds onto a host branch rather than dropping them, providing a much better chance for establishment. New Zealand's epiphytic flora does not have any cacti species, nor any known specialist bird relationships. We do know that some mistletoe species rely on tui and bellbirds for pollination and that the woody vine kiekie might have had a relationship with bats in the past (before they were lost from many areas) but these plants aren't epiphytes - maybe epiphytes like the Pittosporum shrubs species have (or had) important relationships with fauna, it is after all still unclear how their seeds are dispersed. Is anyone out there looking for a research topic?!

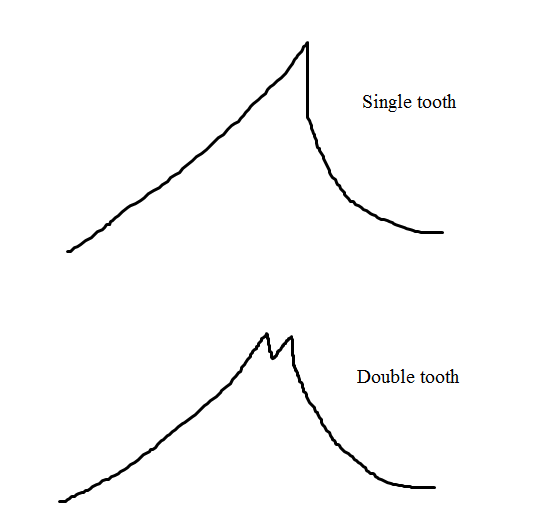

Aotearoa, New Zealand is home to a diverse group of climbing plants called vines. Vines are plants that germinate and have roots in forest soil but, unlike trees and shrubs, cannot stand upright without support from other plants. I use the term "variable vines" because our 25+ species exhibit many different lifestyle and morphological characteristics. We have vines that climb their hosts using: leaves, tendrils, hooks, stems or roots. We have vines that become woody while others are herbaceous. We have vines that reach top of the highest trees and become a dominant feature in the canopy while others only climb a few metres up the trunk of their host tree. We even have one vine species that taps into the stem of its host and takes resources to aid its own growth (Cassytha paniculata)! When it comes to reproduction some vines have a few large showy flowers (e.g. Clematis species), some have many small and brightly coloured flowers (e.g. Metrosideros species) while others are very subtle (e.g. Muehlenbeckia species). Fruiting sees a range of colourful fruit (e.g. Passiflora tetrandra, Rubus species) plain wind-dispersed seeds (e.g. Metrosideros species) or tiny spores (e.g. Blechnum filiforme). The following provides a snap shot of some of this variety. Climbing mechanisms: Photos: C. Kirby Flowering: Photos: C. Kirby Fruiting: Photos: C. Kirby There are two epiphytic species of Asplenium in New Zealand (excluding accidental species) and I must say... I'm quite a fan: Asplenium flaccidum - makawe - drooping spleenwort Asplenium polyodon - petako - sickle spleenwort Both species are drooping ferns that often hang from the forks of host trees or the base of nest epiphytes. Makawe tends to arrive on a host tree earlier than petako and is considered to be the hardier species. MakaweMakawe has very thick fronds with sori that line the inner edge of the pinnae and a prominent central vein. The name makawe also means hair of the head which surely has a connection to the long, flowing form of the fern. PetakoPetako has glossy, sickle-shaped leaves with double-toothed margins. It has dark stipes when mature and rows of sori on the frond underside that sit along the veins. According to Wikipedia, the term 'spleenwort' refers to the use of Asplenium species for treating ailments of the spleen. This was apparently done because the sori resemble the shape of the spleen.

Professor Gerhard Zotz is working hard to connect epiphyte researchers around the world. He instigated the 2013 NZ Epiphyte Workshop and has now confirmed a similar event in Katalapi Park, Chile (scroll about half way down) in December. Katalapi Park (or Parque Katalapi) has 28 hectares of forest and open space with high diversity of ferns and a canopy reaching 30 metres - sounds like good epiphyte country to me! Here are some of their epiphytic species:  Asplenium dareoides Found from the coast to 2000 m above sea level, growing on logs or the ground. Fronds are 7-15 cm long.  Hymenoglossum cruentum Endemic to Chile, this fern is a low epiphyte and is found from 5 to 900 m. Dark green leaves reach up to 30 cm in length.  Hymenophyllum dicranotricum Also endemic to Chile, this species occurs from 2 to 410 metres. Fronds reach 20 cm in length.  Polypodium feuillei Occuring between 5 and 1250 metres, this fern has a thick fleshy rhizome and glabrous leaves tht reach up to 46 cm in length. There are some real similarities between these species and ones that occur on trees in New Zealand: fascinating! I haven't been to Chile recently (or ever... airfare sponsorship however is welcomed) so I have borrowed information and photos from these sources:

References: Information: http://www.parquekatalapi.cl/fileadmin/templates/Katalapi_datos/Flora%20de%20Pichiquillaipe.pdf translated using google translate Photos: http://www.flickr.com/photos/7147684@N03/3439873824/sizes/l/in/photolist-6eYfDo-e9ouA3/ http://www.chileflora.com/Florachilena/FloraEnglish/HighResPages/EH0795.htm http://www.chilebosque.cl/ffer/hdicr.html http://floratalcahuano.blogspot.co.nz/2009/08/calahuala.html |

Subscribe to NZ Epiphyte Blog:Like us on Facebook!

Catherine KirbyI work with NZ's native vascular epiphytes at the University of Waikato. I completed an MSc on epiphyte ecology and the shrub epiphyte Griselinia lucida and have recently published the Field Guide to NZ's Epiphytes, Vines & Mistletoes. Categories

All

Archives

August 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed